News Flash

News Flash

By Poliar Wahid

DHAKA, July 12, 2025 (BSS) – Jatrabari area of Dhaka city was a hotspot of protests, as the student-led movement reached its peak when the Awami League government launched barbaric crackdown on demonstrators to suppress their legitimate demands during the July Uprising in 2024.

Thousands got injured while scores became martyred in the area to free the country from the shackle of authorianism of fascist Sheikh Hasina who ruled the country nearly 16 years.

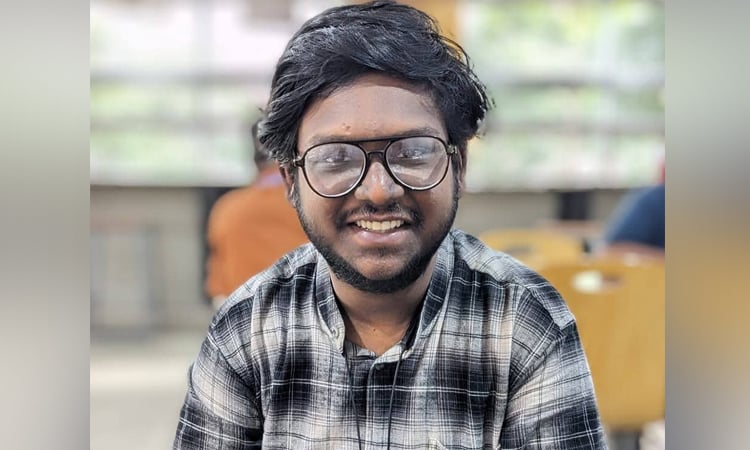

Fayequzzaman Fahad, an English Language and Literature student of the University of Asia Pacific, was one of the frontliners in the area. He along with other coordinators built resistence against the Awami League goons in the area.

Despite sustaining pellet injuries, he didn’t back off. He took to the streets the next day with even more courage.

Fahad was born in 2000 in Nayabazar, Dhaka. Alongside writing poetry, he has developed a knack for translation.

He was vocal in the Anti-discrimination Student Movement from July 15. On July 17, he sustained an injury in his leg. Yet, by July 19, he was back on the streets. That day too, he was struck by splinters.

Fahad’s journey of protest began with the Road Safety Movement in 2018. It reached its height with his spontaneous participation in the July uprising.

In an exclusive interview with Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS), Fahad shared his first-hand experience of the moments of July uprising.

BSS: When did you first join the movement, and where?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: I had been in solidarity with the quota reform movement from the beginning. But I actively joined it on July 15. The strange thing is, that very day my elder brother was unwell. I brought him to DMCH (Dhaka Medical College Hospital). After handing him over for surgery, I stepped outside to catch up on the news of the protests. As I was heading toward the Shaheed Minar, I saw a group of men, only about 50 feet away from me, and chasing two students with local weapons. One of them was struck and fell to the ground. I brought one of the injured students back to DMCH. As I entered the emergency unit, I saw that the attackers -- members of Chhatra League -- had already reached the hospital.

Did they assault people even inside the hospital?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Yes. They attacked the wounded again. That’s when I saw my friend Hasan Enam -- he too had been injured by the Chhatra League. After receiving oxygen, he was released. The attack inside the hospital was an extremely shameful incident. And to be honest, I wasn’t that brave at the time. As the violence intensified, I quietly moved away and sat down in front of the OT where my brother was. That night, July 15, I kept hearing more and more things. And I made up my mind that I couldn’t just sit at home anymore. On July 16, I joined the protests in Farmgate, just near my campus.

On July 16, which universities' students joined you in the protest at Farmgate?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: You know that students from private universities are usually reluctant to public protests. On July 15, I made a public post on Facebook saying we’d be taking to the streets in the Farmgate area. I said, “If you want to join, just show up.” So I was joined by students from -- Daffodil University in Dhanmondi, Sonargaon in Panthapath, and University of Asia Pacific. We all took to the streets together. Students from Science College in Tejgaon were supposed to join us too, but somehow they couldn’t make it.

We wanted to gather under the overbridge in Farmgate. But we couldn’t. At the time, we were around 50 students. Since we weren’t allowed to stand at Farmgate, we moved past Ananda Cinema Hall and took position in front of our campus. Immediately, 10 to 12 Chhatra League members chased and scattered us.

Still, some of us moved toward Dhanmondi 27-- some through Panthapath, others via Manik Mia Avenue. Around 2:30pm, at the Panthapath signal, we were about 100 students. After that, we joined up with students from Dhaka College. That’s when we formed a group.

Did you receive threats from Chhatra League? Did they try to stop you?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Yes, there was a Chhatra League committee in our university as well. One of the senior brothers, linked to Chhatra League, saw my Facebook post and called me. He didn’t directly threaten me, but he said, “You’re like my younger brother. If anything happens to you, I won’t be able to save you. Just stay off the streets for now.”

And I gave him a reply too. I said, “Look, brother, there are eight street dogs in my alley. If one of them barks, the rest bark too. So just because some dog is barking, should I stop going out of my house?”

On July 17, the movement spread across the country. Where were you that day?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: The story of July 17 is a bit different. If I remember correctly, it was Wednesday -- and a public holiday. My home is in Shonir Akhra. That day, I joined the protest in Jatrabari. There was no way I could get to Farmgate on July 17.

That day, I got hit by splinters on my body and on my head. I was injured. I couldn’t make it to the gayebana janaza (absentee funeral prayer) at Dhaka University. And around 7pm that evening, fire was set to the toll plaza.

Who set fire to the toll plaza? Were you there?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: There are different stories about the incident. Some say a father was returning home from coaching with his son, or maybe taking him to coaching. The boy was in Class 8. Suddenly, the police fired tear gas and sound grenades at them. And in outrage over that, some of the guardians set fire to the toll plaza. That’s the version I heard.

When do you think the movement truly turned into a mass uprising?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: I felt it exactly at 9pm on July 17. Because earlier that evening, before sunset, I had already been injured. My friends took me to Anabil Hospital. After getting treatment, I went back home. Around 7pm, my friends called me and said, “The enraged crowd has set the toll plaza on fire.”

One of my friends came to my house. I leaned on his shoulder and left home. When I reached the scene, I saw madrasa students sitting right there on the road.

Now let me ask -- who are “the masses”? It’s not just people like us, the so-called elite. They’re citizens of Bangladesh too. They have just as much right to be here as we do. And it was because they came, because they stood alongside us, that this turned into a true people’s uprising.

It’s only because they laid down their lives so that we could achieve our fair rights. Look at the list of those who were martyred. Count how many were “elite” and how many were from the masses or common people. You’ll see the truth in the numbers.

Now, if certain political parties don’t want to call this a mass uprising, I have nothing to say to them. It’s just saddening. To me, this was absolutely a people’s revolution. And I will always call it a mass uprising.

Even after being injured, you went back to the streets the next day?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: What are you saying! The next day I was even more fired up. After getting hurt, I felt this strange, almost unnatural force or intensity coursing through me.

The main front of the movement had now shifted from Kajla to the Jatrabari fish market area. On July 18, I went straight to that frontline. The police were firing bullets. I saw someone in front of me get hit and fall to the ground. I helped him onto a rickshaw. Others took him to the hospital. And after placing him on the rickshaw, I went right back to the frontline.

But we had nothing in our hands, not even a stick. At one point, a few of our friends were seriously thinking: can we make some kind of weapon out of bamboo? There was a viral video going around on YouTube then about a device made from bamboo!

Were you affiliated with any political party before the movement?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: No, I wasn’t connected to any political party. I’m a poet, after all. However, I was politically aware. Even if we weren’t directly involved in politics, no one is ever really outside of it.

Did you see anyone get injured or killed in front of you? If so, can you share that memory?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: This is a deeply painful memory. It happened on July 19, in the evening -- just as the Maghrib azan was about to begin. A boy in a black t-shirt and a madrasa student in a white panjabi and pajama... it was me, my friend Rahat, and a few others. We were moving forward together.

Suddenly, I noticed a flash of light. Just behind me, the boy in the black shirt was shot straight in the face. The bullet blew out the side of his head. And he collapsed right there.

Unless you saw it with your own eyes, you can’t understand. It was horrific and brutal. Even on battlefields, death doesn’t always look like that. We had no idea where the shots were coming from. No one knew. Who was shooting? From where? We couldn’t see.

Before we could even react, the madrasa boy staggered and fell. A bullet had hit him in the chest and exited through his back. But he was still breathing -- because it hit just one side of his chest.

That was the first brutal killing I witnessed, the most terrifying moment of my life. We had heard people talking about sniper attack. I’m sure that’s what it was.

After that I was shaking. I couldn’t gather the courage to stay in the field. After seeing something like that -- after seeing a body like that -- you can’t even describe what it does to you.

Who do you think fired those sniper shots? Many people suspected they might have been specially assigned individuals.

Fayequzzaman Fahad: The suspicion is definitely there. To this day, we haven’t been able to get to the bottom of it. But suspicion alone isn’t enough -- you need truth, you need proof of it. And we haven’t found any concrete clue yet.

Jatrabari became the biggest hotspot in Dhaka. Protests were happening during the day -- but at night, where were the protesters staying? Who were leading things after dark?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Yes, many people stayed even at night. Protesters used trucks to block the roads, so that no vehicles could enter Dhaka. Because you see, Chittagong Road is essentially the gateway for half the country’s traffic into the city. So, all the trucks were halted. These blockades were mostly maintained during the night -- by the protesters.

We heard that a lot of local students stayed overnight. It’s believed that many of them were politically affiliated as well.

When did political parties start actively participating in the movement?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: The very day I first stepped onto the field on July 16, I saw many political activists already there. They joined the protests right alongside us. Among them were members of Chhatra Dal, Shibir, and others. Especially when we linked up with the Dhaka College students, about half of them were student leaders from different political groups.

Everyone was there except for activists from the Awami League.

You protested in Dhaka. But at the time, did you have any connection with protesters outside Dhaka?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: I had a friend at Noakhali Science and Technology University. They couldn’t organize much of a movement there -- because of the Awami League and government forces, they couldn’t form a strong front. Later, that friend came to Dhaka and joined the protests here.

During the protests, people from different walks of life helped in various ways. Did you witness anything like that yourself?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: On July 18, July 19, and those five days of August, it felt as if Karbala descended upon there. People died here and there. Bullets hit someone out of nowhere. Someone seeking medical care, someone else’s funeral being arranged -- it was chaos. No one can describe it all, not completely.

During those moments, a biscuit shop owner gave away all his food. Others were handing out water on the streets. We were lucky to witness that generosity ourselves.

One of my friends, Rakib -- his sister lives in Australia. She sent him Tk 60,000 one day and said, “Rent an auto-rickshaw and go distribute biscuits and water to the protesters.”

I was always at the frontline. One day I saw Rakib, just like she said, in an auto, handing out biscuits and water. He had my friend Rahat from Jahangirnagar University with him. They gave us a case of water to help distribute.

Now tell me, if this isn’t a mass uprising, then what is? Even those who couldn’t join in person were helping with money. There are thousands of stories like this.

And let me tell you something else -- back in 2018, during the Road Safety Movement, mothers used to cook food at home and bring it to the streets. They didn’t know anyone’s name, but they’d feed us like their own children.

But your dreams can’t be fulfilled without political consensus, right? Have you thought of joining a new political party? Has anyone contacted you?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Yes, a couple of people have reached out. I don’t want to mention their names. But their motives didn’t feel right to me. It didn’t feel truly new, just old letters in a new envelope.

So no, I don’t want to get directly involved in politics. But then again, I’m already in politics. I’m studying more, preparing myself and thinking politically.

Some people are comparing July Uprising to the Liberation War. Some are even calling it the birth of a Second Republic. How do you see?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Look, you can’t pit July uprising and the Liberation War against each other for political gain. Because July happened precisely because the ideals of 1971 had been betrayed.

So if 1971 was the first phase, then this was the second. People fought in 1971 for freedom. And in 2024, we also fought for that same freedom. One is the flower, and the other is its fruit.

On August 5, when Nahid Islam declared the one-point demand from the Shaheed Minar, where were you?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: That day, I walked all the way from Shonir Akhra to Shaheed Minar. And what I saw -- my God -- it was a sea of people. I’ve never seen so many people in my life. And I don’t know if I ever will again.

Where were you on August 5? When and how did you hear about Hasina fleeing? How did it feel?

Fayequzzaman Fahad: Around 11 am, we began heading toward Shahbagh. Students from all schools, colleges, madrasas along the way were joining in. From Shonir Akhra, we started marching toward Kajla, where Mamnunul Haque’s large madrasa is located. There must’ve been around 10 to 12 thousand students. They all joined in. When we reached near the madrasa, chaos broke out. Heavy gunfire started.

That day, there weren’t many people in regular clothes. Almost everyone was wearing white panjabis and pajamas. Right in front of our eyes -- so many people were injured, and many were martyred. I got hit in the head with a splinter, but all I could think was: “We must reach Shahbagh today.”

From there, we moved through Dholai Par, Old Dhaka, Khilgaon, Rajarbagh, and finally reached Matsya Bhaban. There, we saw the army personnel.

They weren’t letting people pass. They said, “Hold your rally here. If there are around a hundred of you, we’ll let you through.” It was around 1pm then. Just then, one of my friends called. He said his brother had just told him -- the Army Chief was about to deliver a speech in one hour. And it was being speculated that Hasina had fled. I felt like I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t believe it.

Finally, we heard fascist Sheikh Hasina fled the country ending her nearly 16-year authoritarian rule. The streets of Dhaka city were flooded with joyful procession of people as student-led mass uprising ousted Sheikh Hasina.