News Flash

News Flash

By Arbak Aditto

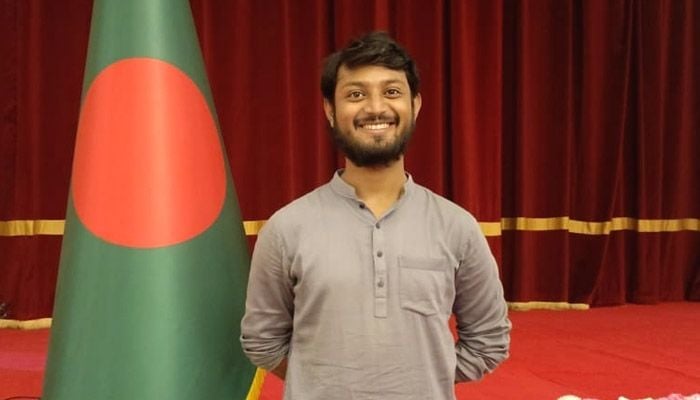

DHAKA, July 12, 2025 (BSS) - Farabi Zisan, a student of BRAC University and one of the key coordinators of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement, believes the fight did not end with the fall of the regime.

“If we leave fascist elements intact within society, that would be a betrayal with blood of martyrs,” he says, calling for the reconstruction of all state institutions and a break from Bangladesh’s old political culture.

A vocal critic of the government long before the uprising, Farabi faced threats, surveillance, and had to go into hiding—but he never backed down. He raised voice against the activities of the banned student organization Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL) within private universities. He also organized several events in solidarity with the oppressed people of Palestine.

During the July movement, he became a target of the ousted fascist regime and was forced into hiding. When the regime tried to suppress the movement with disinformation, Farabi and a few others created a discord server to coordinate securely. Even when facing death threats, he stood his ground.

On the first anniversary of the July Uprising, Farabi shared his experiences with BSS in this exclusive interview. Here is the full interview…

BSS: When did BRAC University students become involved in the movement?

Farabi Zisan: At the very beginning of the July movement, there were some small discussions, but it didn’t spread widely. Protests and small marches were happening with minimal attendance. We hadn't joined yet. One reason was that, as private university students, we didn’t have a strong connection to the quota issue. But my elder brother, who is in the 38th BCS, explained the details to me. After learning more about it, I felt compelled to join the movement.

On July 15, we officially joined. We organized blockades and human chains in front of East West University, in Rampura, and a few other places.

Had you been involved in activism before this?

Farabi Zisan: Yes, for a long time. When Chhatra League first announced a committee at BRAC University, I protested it. Back then, no one stood with me. I was alone, holding a placard in front of the university.

Apart from that, I also participated in the Palestine solidarity movement and others. I have been critical of the Awami League government since my school days, writing on Facebook. That led to internal family meetings and even threats.

Did these experiences influence your participation in the July movement?

Farabi Zisan: Absolutely. After hearing all the details from my brother, I decided to join. But there was a dilemma—our midterm exams were going on. In private universities, these exams are very important. So, I was torn. Meanwhile, Chhatra League was attacking students at Dhaka University and other public universities.

We formed a group and decided to join the movement. First, we posted in an official BRAC University group about our planned program. Our group became the coordination hub for the movement. On July 16, we organized a blockade in front of BRAC and named it “Badda Blockade.” My friend Meher came up with the name. It ran from 8am to 6pm and the university was quite cooperative.

Did you face any interference from police or administration that day?

Farabi Zisan: Yes. Our programme was scheduled until 5pm. Around 2pm, the OC of Badda Police Station called our registrar and proctor, telling them to shut it down by 3pm. I was summoned to the registrar’s office, and a brief argument followed. The registrar insisted on ending by 3, but I argued we had said 5pm. We compromised on 4:30.

But before long, police arrived around 4pm. Meanwhile, we got information that Chhatra League had attacked UIU and AIUB students in Vatara. The atmosphere grew tense. I spoke with the OC and convinced him to let us continue a bit longer. He agreed, and we were able to run the program until 5pm.

So, the police didn’t use any force?

Farabi Zisan: Usually, police avoid using force on private university students because most of us come from privileged families. They fear backlash if they harm someone who turns out to be a minister’s or businessman’s child.

After the event, though, UGC announced that no university would remain open. That put us in doubt about the next day’s programme. I called the registrar's office that night to ask if the gate would be open. They didn’t respond.

Around midnight, they called and informed us that they wouldn’t cooperate and the campus would be closed. The next morning, I showed up early. Since staffs enter early, the gate was open. A few of us entered with the staff and got our placards ready. Around 9am, we stood at the gate with placards.

What happened when the police arrived?

Farabi Zisan: “A patrol team of police was passing... We stayed within our boundary, but they came and said we couldn’t stand there because the university was closed.” It escalated quickly. We contacted our security in-charge and told him that Chhatra League members were allegedly gathering nearby with weapons and might attack.

We requested the main gate be opened for safety. He said he had no such instructions and could lose his job. I asked him one last time—will you open the gate or not? He said no.

We decided to break the lock. We climbed the gate and searched for something to break it. Eventually, we found a “No Parking” steel pipe and hit the lock about 50 times. My hands went numb. Finally, the lock broke, and we opened the gate.

Police forces arrived and gave us a five-minute ultimatum. They said, “If you don’t leave, we will shoot.” I responded with a counter ultimatum: “You return to the police station. Otherwise, be ready to face counteraction.”

They left—but within two minutes, sound grenades and tear gas started flying. I personally took 20 to 25 rounds of tear gas.

Were you afraid? Did you disperse?

Farabi Zisan: Public universities have dorms, so mobilizing is easier. For us, students live all over the city. Most of us don’t even know each other because of the open-grade system. So we realized we needed a different approach.

We thought—why not coordinate all private universities together? Even if a few students come from each, it adds up to hundreds. We formed an unofficial forum called the “Private University Alliance,” with about 18 universities.

After the police attack, we messaged the group. Soon, students from Badda and Rampura came marching in support. We exited campus to join them. The police split—some stationed near Canadian University, others near Hatirjheel.

I was struggling to breathe from the gas. My friend Oitijhho and I took a student who’d been shot into the medical center. He died on the street. We wrapped his body in the national flag and brought it into the university premises.

That was the first time I saw someone die from gunfire in our movement. His flag was removed, and I saw him staring at the sky, chest riddled with pellets and bullets. His parents didn’t even know he was dead. Just a college student in his second year. We were shaken. We asked—Is this throne so important that it demands lives?

My mother heard I was injured and came to BRAC on a rider biker. My family took me away in a CNG. Most roads were under student control. We used ID cards to get to Mohammadpur. My phone had been destroyed by a bullet. I couldn’t even activate my SIM. That night, the police started conducting raids. I used my brother’s number to check in on friends.

During the curfew, we heard that Nahid Bhai and others had been taken to DB. TV scrolls were our only source of updates. Later, we learned they were moved from Gonoshasthaya Hospital. I had planned to go meet them to discuss strategy. But before I could, they were taken away again.

So, we held our own program on the 26th—nothing major, just at East West. On the 27th, we debated what to do next. We didn’t hold any program that day. On the 28th, there was a small one. We tried involving faculty members at this stage. We decided BRAC would not organize anything for the next three days, even if other private universities did. We felt our plans were leaking. Everything we discussed, police somehow found out.

A friend suggested we follow the Taiwan model. So, on the night of 28th July, we launched a Discord server. We carefully vetted members—cross-checked data, verified university info. Within two days, we added around 8,000 members.

All our plans were now secure. We would post misleading info on public groups and direct real instructions through the server. The police couldn’t predict our moves anymore. We returned to action. The non-cooperation movement was in full swing. We organized blockades.

On August 4, my brother came and urged me to leave. I was under pressure—always on the run, not going home, hiding in different places. Intelligence agencies were looking for me. They even arrested four people with similar names. On the 7th, after Hasina’s fall, I met with Sarjis Bhai. He said he’d seen my picture at the DB office. They had clear orders to arrest me.

On the 4th, we had planned the long march to Dhaka for the 6th—but it got moved up for 5th August. The next day, I saw the army deployed everywhere. No way to move. But soon, reports came in: large processions from Uttara, from Jatrabari. The roads began to change. Then came the army chief’s speech. And finally, the news of fascist Hasina’s fall.

What are your hopes for the new Bangladesh?

Farabi Zisan: The people took to the streets to free themselves from fascist and authoritarian rule. They’ve begun to dream of a corruption-free, equal society. This is the time to rebuild the country. We must breakdown the old political culture.

As Bangladeshis, it’s time to redefine our national identity. If we don’t restructure our institutions and if we allow fascist elements to persist in our society, it would be a betrayal of the martyrs’ blood. We want everyone to come together to rebuild this country.