News Flash

News Flash

By Arbak Aditto & translated by Tausiful Islam

DHAKA, July 10, 2025 (BSS) – The students of private universities played a significant and courageous role during the July mass uprising, 2024. Once they joined the movement, it quickly spread to schools, colleges, and eventually across the country. Their participation marked a turning point, a new trajectory for the movement.

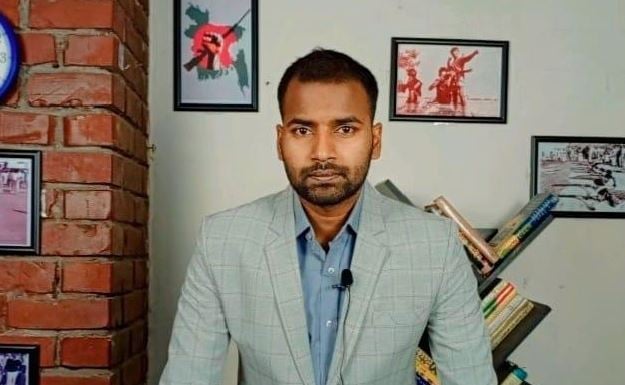

One of the key organizers of the July mass uprising, Hasibul Hossain Shanto, shared his experience in an exclusive interview with the Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS).

Shanto is currently a student of English Language and Literature at the North South University. As his father was involved in politics, Shanto grew up with a clear understanding of the country’s political landscape. Over time, he began charting his own political path.

A vocal critic of the ousted Awami League’s authoritarian rule, Shanto believed that Bangladesh urgently needed a major transformation -- not a cosmetic change, but a foundational one. The student-led July uprising offered that very opportunity.

During the peak of the July uprising, he risked his life to build a strong resistance on the eastern side of Dhaka (Jamuna-Baridhara-Badda).

BSS: Private university students are rarely seen in major mass movements. When it comes to challenging power or holding them accountable, we typically don't see much presence from private university campuses. But in the July uprising, private university students played a significant role. Was this a sudden decision for you all to join the protests?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: The quota reform movement actually began back in June, but it grew into a full-scale movement around mid-July. The real turning point came on July 15, when now banned Chhatra League attacked general students at Dhaka University. That incident pushed the movement beyond the boundaries of DU and spread to other public universities. Thus, it became a nationwide uprising.

It’s true that political activism doesn’t usually exist in private universities. There's no real intention among students here to engage in politics, and frankly, not many politically minded individuals even end up in private universities. That’s the reality. But just because political activism isn’t practiced openly doesn’t mean we lack political awareness.

In fact, private university students played the biggest role in this movement. Once they joined, it spread like wildfire to schools, colleges, and all over the country. It gave the movement a new momentum.

When Sheikh Hasina called the quota reform protesters “Razakars” on July 14, the reaction was immediate. We saw the response across social media and in educational institutions throughout the country. We, too, expressed our anger in our own ways. I remember posting on Facebook:

“If being a Razakar means standing with 180 million people, then I’m proud to be one.”

Around the same time, there were serious discussions in our student groups about whether we should formally join the movement. The next day, on July 15, we showed up on campus. A few of us gathered at Gate 8. We bought some art paper, made a few placards. There were about 60 or 70 of us.

Then, more people joined in. We moved toward Jamuna Future Park. We held a two-hour blockade there and ended our first programme. After that, a few friends and I decided to go to the Dhaka University campus.

But I didn’t have the mobile number of Sarjis Bhai (Now National Citizens’ Party leader), so I reached out to a friend in media. When we arrived, clashes were already happening. There was an attack at the VC Chattar, so we moved toward Raju Sculpture. From there, I called Sarjis Bhai, and then we rushed to Dhaka Medical College Hospital to help the injured.

Did your family allow you to take part in the movement? Private university students usually come from more privileged families, and parents are often very concerned about their child’s safety.

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: Abba knows there's no point in trying to stop me. My father is involved in BNP politics. But honestly, I was never drawn to these conventional political parties. I didn’t join any party. However, I’ve always been critical of the government from time to time.

After the farcical national election, I once went to lock the doors of the Election Commission building. I even took a large padlock with me. But some well-wishers convinced me not to do it. They warned it could cause serious trouble, and that it wasn’t the right time.

Anyway, Abba just told me to be careful.

After I gave a fiery speech in front of Jamuna Future Park, the police showed up at our village home. They asked around. Later, they came to our apartment in Bashundhara too and conducted a search. During that time, I kept my phone turned off and stayed at a nearby acquaintance’s place. I used VPN to stay active on Messenger and WhatsApp groups.

We had two or three Messenger groups. One was a common platform for all private university students. Around 40-50 of us were actively coordinating there during that time. We treated that group as our representative coordination channel. We used it to stay in touch with everyone.

After six people were killed on July 16, everyone got alarmed and even more motivated to take part in the movement. People really started stepping up. That day, in front of Jamuna, I said something like: “The student body is a burning flame. Don’t play with fire -- the consequences will not be good.” That was my message.

After July 16, we didn’t announce any new formal programs. We just said: “We’ll all go to TSC at Dhaka University on July 17.” There was a gayebana janaza (funeral prayer in absentia). Some students lit candles at North South University that day. The rest of us went to TSC.

Did you face any trouble getting to the streets?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: Yes, we did. When we reached Shahbagh, we saw people holding sticks and rods, standing next to the police. They were from Chhatra League and Jubo League. Somehow, I slipped past the crowd and made it to the campus.

We went to the VC Chattar and joined the gayebana janaza. After that, we carried the symbolic coffins toward Raju sculpture. By then, clashes had already broken out at Mall Chattar. The students were fighting back, resisting the attacks. We joined them.

Tear shells were being fired; many were feeling the burning in their eyes. We lit small fires with paper and trash around us to ease the stinging. At one point, Hannan Bhai (Abdul Hannan Masud) was brought in. He was badly injured, with bloodstains on several parts of his body.

But we had no way to get him to a hospital -- the main road had turned into a warzone. A few of us tried to take him out through the pocket gate beside Zia Hall, but we were attacked there too. The attackers were hurling heavy chunks of broken bricks. We had no choice but to retreat.

We came back and laid down on the grassy patch in front of Bijoy 71 Hall. After a while, a rickshaw came by carrying some biriyani -- we used that rickshaw to send Hannan Bhai to the hospital.

We stayed on the DU campus till about 6:30pm that day. Then I called Sarjis Bhai. I told him: “Bhai, don’t worry. Tomorrow, we’ll shut down the entire eastern side of Dhaka. You just keep the movement going on your end. We’ll show how to paralyze the east.”

I still have the recording of that call. Our focus, from that point, was single-minded: a one-point movement. If the state kills its own citizens, it loses all moral right to govern. There would be no negotiation.

And after that -- did you return home?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: Yes. That evening, after getting home, I sat down with a few others to plan our next steps. We finalized a programme and I recorded a 9-minute video. I uploaded it on Facebook that night.

Meanwhile, in our private university group, there was ongoing discussion. The main idea being tossed around was that we, the students from private universities, should impose a blockade in the Rampura area.

I responded by saying: “Instead of focusing on one single location, what if we carry out smaller, simultaneous blockades at multiple points? That would have a much greater impact.”

It’s not just about how many students were in one blockade. What matters more is how many different points across the city were blocked. The broader the disruption, the more alarming it becomes for the government. So, if we really want to do something effective, I said,

we have to spread this movement further, multiply its reach.

What was decided?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: We decided to hold blockades in front of our respective institutions. On the morning of July 18, we went to North South University campus. The police showed up, and there was a heated exchange. They told us that if we moved today, they’d open fire. They said they wouldn’t have a choice. I told the students, "We’re not afraid of the police. If they shoot, I’ll be the first to take the bullet."

We moved and took position in front of Jamuna Future Park. Bobby Hajjaj sir joined us there -- he’s also a teacher at North South University. Others from civil society joined us as well. That’s when we got the news that students in front of BRAC university were being attacked.

We decided to march toward BRAC. As we reached Natun Bazar, students from UIU, UITS, and Presidency University joined us. Until then, they hadn’t been able to get onto the main road due to police obstruction. But when they saw our procession, they joined with huge excitement.

At that point, our procession had over 15,000 people. Just as we crossed Notun Bazar and reached Bashhtola, they opened fire on us. Tear gas was launched. I panicked a bit -- there were school and college kids in our march, most of them from Bashundhara. Physically, they weren’t capable to deal with that kind of situation. They didn’t have the mental strength we had.

I didn’t want them to go through something so much horrifying. Even so, we began resisting. At one point, I fell down near Uttar Badda -- I realized a brick had hit my head. Suddenly, everything felt still. I went near a shop shutter and called Sarjis bhai. I told him the situation and asked if we should fall back.

He said, "The police just want to scatter you. Don’t be afraid. Raise your hands and tell them not to shoot." By then, there was blood everywhere on the street. Hundreds were injured. Since I was leading, I had a responsibility. I was still leaning against a shutter, trying to stable myself. We had a microphone on a rickshaw chanting slogans, and I saw bricks chips everywhere. The rickshaw puller had abandoned it. The rickshaw with the microphone was just standing in the middle of the road. It was chaos. One of our students began peddling the rickshaw. I picked up the microphone and spoke directly to the police: "Please don’t shoot. We want to talk."

Eventually, we managed to push forward. As all of us moved together, the police got cornered and took shelter inside Canadian University.

Then we moved the injured to IUB’s emergency room. Many IUB students were already there. If it were just one or two, we could handle it -- but hundreds of injured? It was total devastation. Panic on one side, a steady stream of injured on the other. What can I say—it’s hard to put that situation into words. After getting primary treatment at IUB, I came out looking for a rickshaw. That’s when three or four men showed up with sticks -- they were from Chhatra League. They had marked me.

As soon as I saw them, I went back inside IUB and later exited through the north gate to return home. Once home, I opened the internet -- and saw sheer horror.

There were messages in all the groups, people crying, describing what had happened to them. I felt so guilty. I had said, "If there’s gunfire today, I’ll be the first to take the bullet." But I didn’t get shot -- I just got injured.

That’s when I decided -- there’s no turning back anymore.

We must move toward a single-point demand, no matter what.

What did you do after that?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: On July 19, a curfew was imposed. We decided we would break the curfew. In the meantime, we raised some funds. Then we contacted the families of those who were seriously injured and sent them amounts like Tk 20,000 or 25,000 each.

That day we took position in front of Jamuna Future Park. We stayed there from 9am till 5pm. On the day, they fired on us from a helicopter. I spoke about the changes needed in the constitution and our democratic rights. We demanded the formation of an independent commission.

In the evening, when I returned to campus, I heard that Babul Commissioner had attacked our students. But we couldn’t get there. I told those who were already there to take the injured to Evercare Hospital.

When the police heard we were going there, they kept coming to look for us. Every time they came, we would move to a different floor. Around 1am, we decided to leave for home. But thinking home might not be safe, I went to a house on a nearby street instead.

We stayed in that house from July 19 to July 24. During that time, there was no internet. We did some graffiti and small actions. We kept in touch with others over the phone.

What decision did you make after that?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: We decided we’re going to hold a media briefing. It didn't feel right to us to hide like this anymore. At the time, the police were carrying out block raids. The only kind of program we could manage then were symbolic ones, like absentee funeral prayers. But honestly, those didn’t have much impact.

We held a press briefing. But there was no real media coverage. Just a few seconds of clips here and there -- none of what we actually said made it to the air. Around that time, a 9-point demand was published. Later, we held another press conference near the News24 office. Intelligence agency people were present that day. At that conference, we urged people to take to the streets.

On July 25, while doing graffiti near Gate 8 of North South University, the police chased us. The next day, plainclothes security personnel came to arrest us. We took shelter inside the campus. That day, the administration of North South University was under pressure to hand us over. At that point, I shouted: “If there’s any attempt to turn us in, there will be dead bodies here.”

On July 27, I spoke to Sarjis bhai. Later that day, I saw online that he had been picked up. That’s when I switched off my phone. That same day, my friend Nafisa, a law student, was picked up by the Detective Branch, because of me. During the movement, I had talked to her nearly 27 or 28 times. The DB asked her for my home address. That’s when I started planning to leave Bashundhara.

Late that night, on July 27, I left my house and went to an uncle’s place. Our lives were under serious threat. It was around 11pm. But that uncle refused to let me stay. So, I went to another cousin’s house. I turned my phone off and somehow made it through the night there. Around 6am, I booked an Uber and headed for Rayer Bazar near the Beribadh area in Old Dhaka.

Were you still in touch with the others?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: Yes. We were still connected to our network and continued announcing programs. On July 28, our teachers expressed solidarity with us. Several of them were also picked up.

On August 1, we held a protest at Gate 1 of North South University. The police didn’t interfere much that day. We carried out our program for about an hour and wrapped up.

On August 2, we gathered again in front of the Jamuna gate. I gave a speech that lasted about three and a half minutes. I called on people from all walks of life to come out into the streets. On behalf of Janatar Mancha, we declared Hasina’s government unwanted.

We also urged the heads of every armed force to declare solidarity with the people.

On August 3, we went to the Shaheed Minar. Nahid bhai (NCP Convener) announced the single-point demand there. That was as far as the day went.

The next day, we took position again at Gate 1 of North South University, in support of the non-cooperation programme. So many people joined us that day. Some brought foods, others brought water, some even cooked traditional sweets and brought them, not for themselves, but for us.

What did you do on August 5?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: We could not sleep on the previous night. In the morning on August 5, we began gathering at Gate 1 of North South University. There were around 70 of us. When Nafsin Azrin stepped forward, the police launched an attack.

At the same time, we came to learn that members of Chhatra League, Jubo League, and Awami League were gathering in multiple layers to attack us. We investigated and found out it was true. They were well-prepared. They were definitely going to attack.

Meanwhile, rumors started spreading in our area that Nahid bhai (Nahid Islam) had been killed. The message was clear: Nahid is dead, meaning we had no leadership left.

We couldn’t reach Sarjis bhai or the others on the phone either. We were completely disoriented. We didn’t know what to do.

Just then, we heard a massive procession was coming from Uttara. We were joined by students from Presidency University, Green University, and all the neighboring institutions. Even on that day, there was a brutal attack.

How do you envision this new Bangladesh?

Hasibul Hossain Shanto: Politicians should prioritize their responsibility, not their power. Misuse of power severely hampered democratic process We need to change ill-political culture to build a new Bangladesh.