PARIS, Sept 21, 2021 (BSS/AFP) - Alzheimer's disease, the most common form

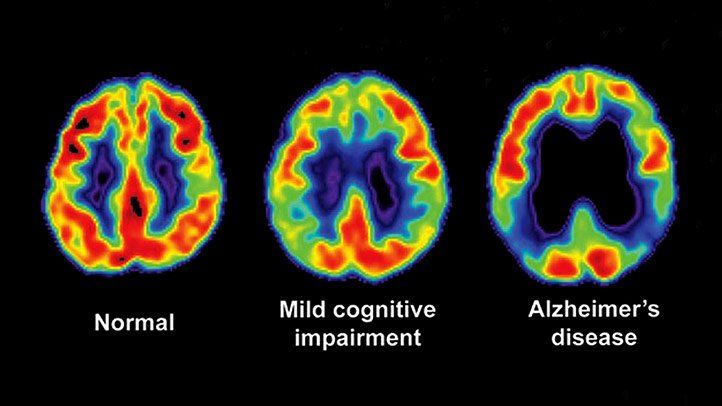

of dementia, is characterised by brain lesions that can cause devastating

memory loss and behavioural changes. It affects some 30 million people

worldwide.

Decades of research have failed to produce a cure, prevention or reliable

treatment.

On World Alzheimer's Day, expert Bruno Dubois tells AFP why one of the most

promising avenues for treatment depends on early diagnosis.

The following are excerpts from the interview:

- How close are we to an effective treatment? -

The key is making a diagnosis as early as possible, because we are nearly

certain to have medications that will work better the earlier they are

prescribed.

These treatments act on the lesions associated with Alzheimer's but are

only effective in the first phase of the disease. By the time a patient has

advanced symptoms it's too late, we can't undo damage already done.

- How can you spot Alzheimer's before symptoms appear? -

One promising avenue for early diagnosis is detecting biomarkers --

biological signatures of lesions caused by the illness.

Before, we needed sophisticated brain imagery or spinal taps to detect

them. Today, blood tests are starting to give promising results (across large

cohorts), though they are not yet reliable on an individual level.

We may be soon be able to identify people at risk who are symptom-free but

have lesions, this is still an area of active research.

- Is this method alone enough to diagnose someone? -

No. We are not at all ready to use these techniques in clinical practice.

The presence of lesions does not necessarily mean that the disease will

develop, so there is a big risk to seeing all patients with lesions as

potentially ill.

We don't want to expose people to potentially dangerous medications to

prevent an illness they may never contract in the first place. You can

destroy a person's will to live by telling them they're going to get

Alzheimer's, when in fact they may never get it at all.

For an older patient, say 75, with memory problems confirmed by tests, who

gets disoriented in time or in a new neighbourhood, and who can't remember

recent events, in that case biological tests for lesions are justified.