HARARE, July 20, 2019 (BSS/AFP) – Blessing Chingwaru could barely walk

without support when he arrived at the specialist Rutsanana clinic in Harare

complaining of chest pains and fatigue.

Weighing a skeletal 37 kilogrammes (5.8 stone), the HIV-positive motor

mechanic knew something was wrong.

He was immediately given a number of tests and told the bad news: He was

also suffering from advanced-stage tuberculosis. Dual infection by HIV and TB

is a notorious killer.

“My health was deteriorating and I kept wondering why,” Chingwaru, 29,

recalled at the clinic.

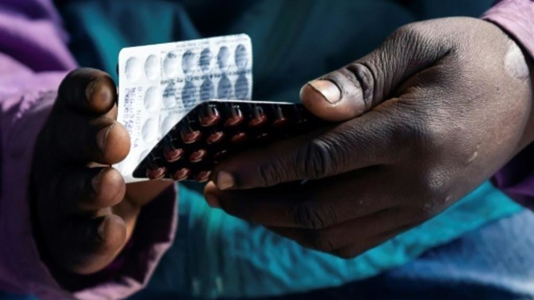

Within hours of the diagnosis, Chingwaru was given free treatment and

nursing care.

In a country where more than a dozen people die each day from TB-related

sicknesses, it was a rare example of efficient public healthcare.

The Rutsanana Polyclinic in Harare’s poor suburb of Glen Norah, which

Chingwaru visited, is one of 10 pilot clinics in the country offering free

diagnosis and treatment for TB, diabetes and HIV.

The clinic, which opened in 2016, is staffed by 24 nurses and currently

treats 120 TB patients.

Among the million-plus people living with HIV in Zimbabwe, TB is the most

common cause of death, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

HIV-positive people, and others with weakened immune systems, are

particularly vulnerable to contracting the infection.

After Chingwaru’s initial visit in February, doctors had feared for his

life.

But following five months of careful treatment Chingwaru has gained 15

kilos.

“Everything I need, I get here,” said Chingwaru, forming fists with both

hands to show off his regained strength.

– Economic and financial crisis –

In a country where public health services have practically collapsed,

containing the spread of TB has been a persistent struggle.

Zimbabwe has been stuck in a catastrophic economic and financial crisis for

decades and its doctors are underpaid and under-equipped.

Although TB treatment is free, the annual number of TB infections in

Zimbabwe remains among the highest in the world.

The contagious infection is usually found in the lungs and is caught by

breathing in the bacteria from tiny droplets sneezed or coughed out.

As HIV-positive people are so vulnerable to TB, the clinics have followed

the advice of WHO officials to link TB testing and treatment with HIV

prevention programs.

– ‘Catastrophic costs’ –

Close to the main gate of the Rutsanana clinic, a green self-testing HIV

tent has been erected to encourage people to check their status.

The clinic also offers voluntary HIV counselling and antiretroviral

treatment.

Sithabiso Dube, a doctor with the medical charity International Union

Against TB who heads the TB and HIV programme, said people with diabetes also

have a higher risk of developing TB, so patients are tested for both

diseases.

“Instead of going to seek diabetic care at one clinic and TB care at

another, they are able to get these services in one place,” Dube told AFP.

Because services are free “they are able to cut down on what we call

catastrophic costs to the TB patients,” she said.

Largely funded by a US Agency for International Development (USAID)

programme, the pilot clinics have become lifesavers for the poor — but only

if they happen to live near them.

The vast majority of the population have no access to the one-stop clinics.

As a result there are plans to scale up the programme, with another 46

similar centres to be rolled out across Zimbabwe.

Rutsanana clinic matron Angela Chikondo said the programme was crucial to

minimising complications among TB and diabetes patients.

“If one is on TB treatment and also has diabetes, and the diabetes is well

controlled, chances of recovering are very high,” she said.